Rubens Cain Slaying Abel, around 1608-1609

Rubens masterpiece "made for market" Artist chose "cheap and cheerful" wood

--The Art Newpaper

January 2012--The restoration of a painting by Rubens from London’s Courtauld Gallery has revealed that the work was probably not a commission, but created for the speculative market. Cain Slaying Abel, around 1608-09—one of the most significant works by the artist in the Courtauld’s collection—is due to go back on display next month, following an 11-month project to clean the work and address structural issues. The money for the treatment came from the Bank of America Art Conservation Project, which launched a conservation grants programme in 2010.

Although scholars have long known that the painting belonged to a group of works produced following an eight-year trip to Italy, where Rubens studied pieces by Michelangelo and Caravaggio, a dendrochronological analysis of its panels revealed that the work was created almost immediately upon the artist’s return to Antwerp. The fact that the oak boards are made from sapwood (the outermost, younger wood) has led conservators to speculate that the painting was for the art market. “It was typical for a client to buy panels for the artist, and in doing so, [the client] would normally buy the best quality materials,” says the conservator Kate Stonor, who explains that sapwood is not ideal because it is soft and sweet, making it prone to woodworm. “We think Rubens bought the panels himself and chose the ‘cheap and cheerful’ option, knowing that the work was for the art market,” says the conservator Clare Richardson, who also worked on the piece.

Infra-red imaging revealed line drawings beneath a tree in the background, which are uncharacteristic of Rubens and may be the work of a landscape artist.

Aside from areas of paint loss and layers of varnish that had yellowed, and, in some cases, became opaque, the most pressing concern related to the work’s cradle, a late 19th- or early 20th-century addition that was restricting the panel’s natural movement and was full of woodworm. The glue was beginning to fail and the panel was starting to pull away from the cradle, causing an unnatural inward curve of the boards, which resembled a miniature mountain range. This curvature also caused disfiguring lines that cut through the figures’ marble-toned flesh.

“One of the greatest benefits of the [treatment] is that we are no longer fighting with the condition of the work… the piece now really speaks for itself,” says Caroline Campbell, the curator of paintings at the Courtauld.

The Courtauld’s chief conservator, Graeme Barraclough, has constructed a bespoke frame with a built-in support system that will “accommodate the natural curvature of the board, allowing it to move without imposing stress on the painting”, unlike the cradle that previously kept it in place. “It’s like support hose, rather than a rigid corset,” Stonor says.

SOURCE: www.theartnewspaper.com

Recent Articles

.png) FILIPINO ART COLLECTOR: ALEXANDER S. NARCISO

FILIPINO ART COLLECTOR: ALEXANDER S. NARCISOMarch 2024 - Alexander Narciso is a Philosophy graduate from the Ateneo de Manila University, a master’s degree holder in Industry Economics from the Center for Research and...

An Exhibition of the Design Legacy of Salvacion Lim Higgins

An Exhibition of the Design Legacy of Salvacion Lim HigginsSeptember 2022 – The fashion exhibition of Salvacion Lim Higgins hogged the headline once again when a part of her body of work was presented to the general public. The display...

Jose Zabala Santos A Komiks Writer and Illustrator of All Time

Jose Zabala Santos A Komiks Writer and Illustrator of All TimeOne of the emblematic komiks writers in the Philippines, Jose Zabala Santos contributed to the success of the Golden Age of Philippine Komiks alongside his friends...

Patis Tesoro's Busisi Textile Exhibition

Patis Tesoro's Busisi Textile Exhibition

The Philippine Art Book (First of Two Volumes) - Book Release April 2022 -- Artes de las Filipinas welcomed the year 2022 with its latest publication, The Philippine Art Book, a two-volume sourcebook of Filipino artists. The...

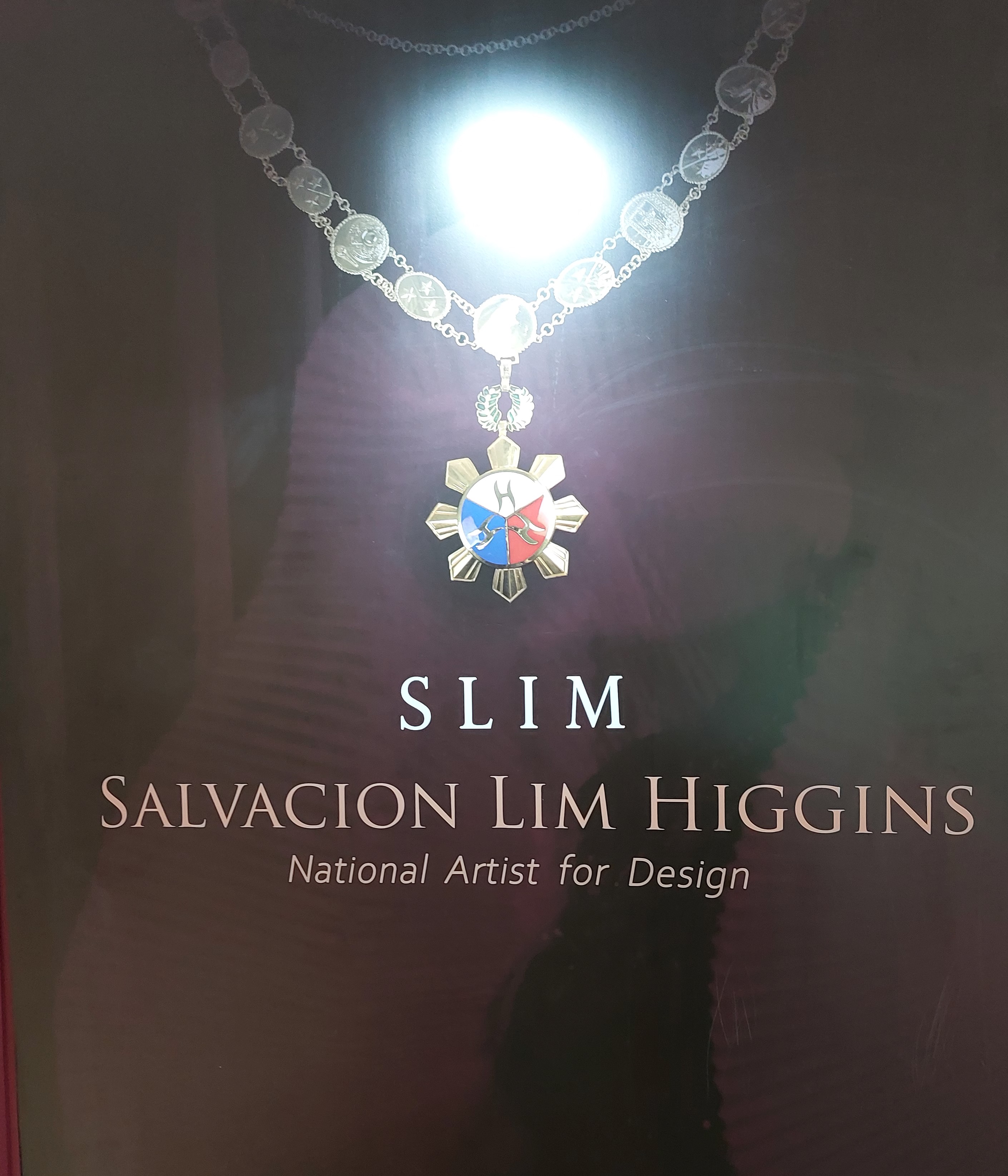

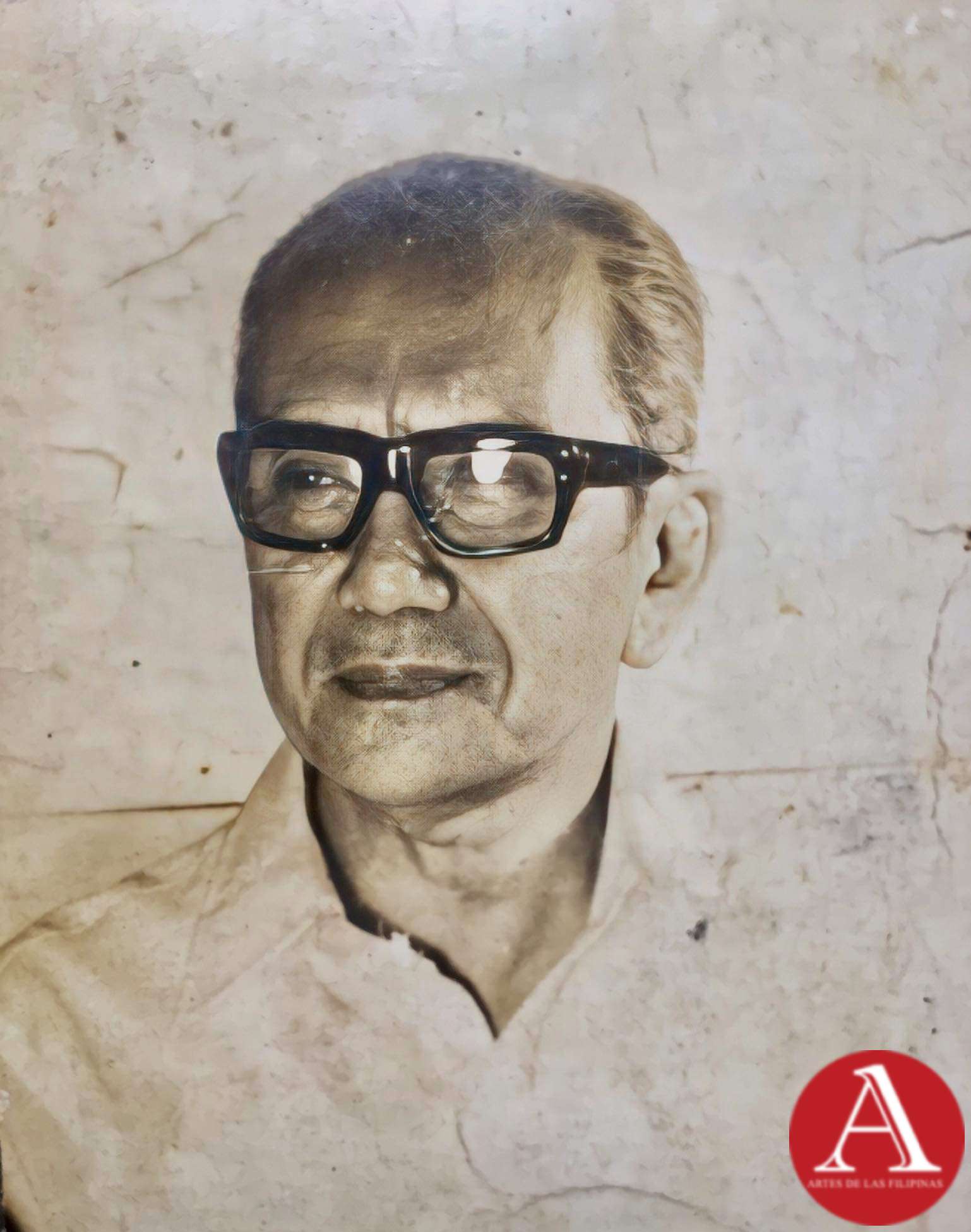

Lamberto R. Hechanova: Lost and Found

Lamberto R. Hechanova: Lost and FoundJune 2018-- A flurry of renewed interest was directed towards the works of Lamberto Hechanova who was reputed as an incubator of modernist painting and sculpture in the 1960s. His...

European Artists at the Pere Lachaise Cemetery

European Artists at the Pere Lachaise CemeteryApril-May 2018--The Pere Lachaise Cemetery in the 20th arrondissement in Paris, France was opened on May 21, 1804 and was named after Père François de la Chaise (1624...

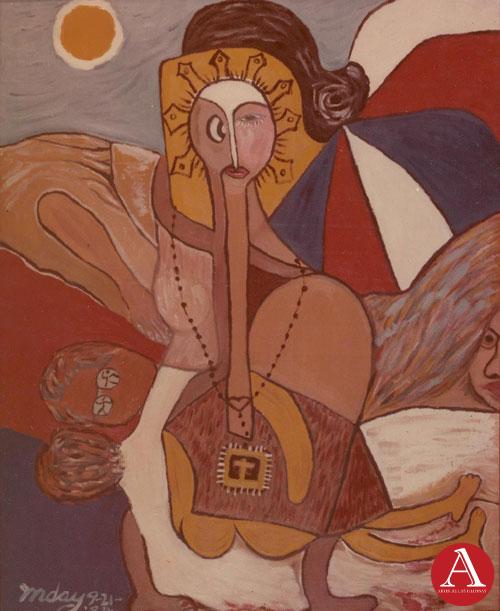

Inday Cadapan: The Modern Inday

Inday Cadapan: The Modern IndayOctober-November-December 2017--In 1979, Inday Cadapan was forty years old when she set out to find a visual structure that would allow her to voice out her opinion against poverty...

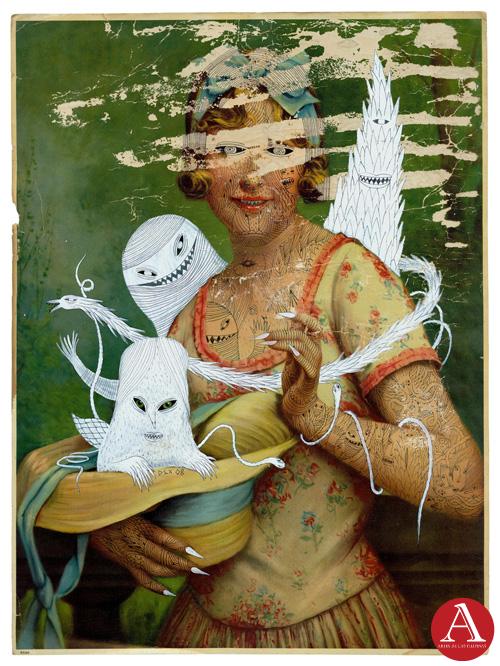

Dex Fernandez As He Likes It

Dex Fernandez As He Likes ItAugust-September 2017 -- Dex Fernandez began his art career in 2007, painting a repertoire of phantasmagoric images inhabited by angry mountains, robots with a diminutive sidekick,...

Noel Soler Cuizon's Gesamtkunstwerk and Everything in Between

Noel Soler Cuizon's Gesamtkunstwerk and Everything in BetweenApril-May 2017—The public exhibition of Noel Soler Cuizon’s works began in 1987 when he was a member of Hulo, a group of alumni students of the Philippine Women’s...